Over a hundred years ago, the monopoly business utility model emerged as the one that could attract sufficient capital to electrify everything.

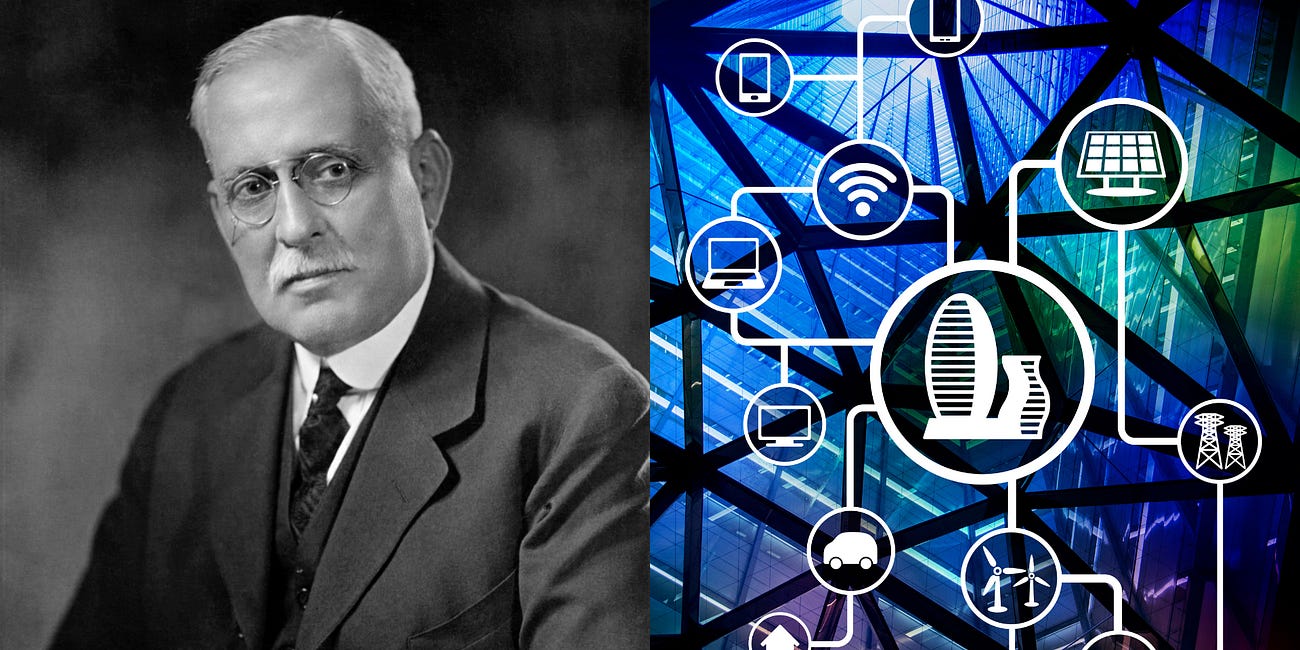

The monopoly utility business was championed by Thomas Edison’s protégé and early leader of ComEd in Chicago, Sam Insull.

It worked. By mid-century, most Americans had power.

But today, competition for generation and retail have shown that monopolies are not necessary. Texas is a poster child for for competition but even Texas has little competition on the distribution side — and the cost of distribution is skyrocketing with no ability for competitors to offer alternatives that could save consumers money.

The monopoly model literally rewards utilities for spending more capital, even when smarter, cheaper options exist.

In my conversation with economist Lynne Kiesling, we traced the arc from Insull’s vision to today, and talked about where the system is showing serious signs of distress. And we discussed how that could change…

How We Got Here: Edison’s Machine

Edison designed complete systems, from generators to the lamp in JP Morgan’s house. Insull scaled that model in Chicago, betting on economies of scale (bigger plants) and scope (serving factoreis, homes and electric trolleys together to increase system utilization and load factors).

That became the vertically integrated monopoly: a single company, fully integrated, would keep costs low. Legislatures around the country formalized it, spreading the monopoly-utility model far and wide.

It was the right model for the time. America needed electrification, and investors needed stable returns.

“Economies of scale and scope… that’s your natural monopoly right there.” - Lynne Kiesling

Why It Worked Then and Why It Doesn’t Now

The framework assumed three things:

Bigger plants are always cheaper.

Vertical integration and central planning are essential.

Utilities should earn guaranteed returns on new capital.

That fit a world that wasn’t yet electrified and needed massive centralized power plants. But two revolutions were disruptive to the monopoly model:

Gas turbines: By the 1980s, combined-cycle plants made smaller, flexible generation competitive and lower cost than bigger centralized plants. The “dash to gas” in the 2000s proved it.

Digitalization: Sensors, controls, and standards cut transaction costs. Coordination no longer required vertical integration.

Price Discovery: The Linchpin

Economist Friedrich Hayek described prices as a “system of telecommunications.” ERCOT proves it daily. When scarcity prices spike, batteries discharge, generators ramp up, demand response kicks in. Investors see those signals and commit capital for more resources.

“Markets are a discovery procedure… trial and error with your own capital is how we get the most benefit.” - Lynne Kiesling

Every bet on future conditions shapes tomorrow’s incentives. That’s why Texas leads in storage growth, retail innovation, and is attracting new gas peaker plants, too.

But here’s the catch: we don’t allow price discovery work at the distribution level.

The Last Monopoly Mile

Transmission and distribution remain monopoly domains. Under today’s rules, utilities earn more by spending more. Propose a $50 million substation, get it approved, earn a return. But what if a portfolio of distributed resources (e.g. batteries, EV charging, demand response) solved the same problem for half the cost?

In most states, including Texas, that option isn’t tested. Regulators just green-light the $50 million.

That’s why Lynne calls for “quarantining the monopoly”: keep exclusive rights to the poles and wires, but open competition for solutions at the grid edge.

Final Thoughts

Texas already showed the world that wholesale competition works. Volatility spurs investment, spreads risk to investors, and drives down long-term costs.

The next frontier is distribution. If we quarantine the monopoly to the wires while opening structured competition for everything else, we’ll see faster innovation, more reliability per dollar, and lower bills.

That’s the Texas way: pragmatic, innovative, and willing to lead.

This is just Part 1 of my conversation with Lynne Kiesling. Next week in Part 2, we’ll dive into data centers, AI demand, and why risk allocation will define the grid’s future.

Timestamps

00:00 – Introduction

02:30 – Why history matters today

05:00 – Edison’s vision for a fully integrated electric system

07:30 – Insull’s bargain: regulate us but grant a monopoly & don’t municipalize

10:30 – Was monopoly the right solution then?

16:30 – Natural monopolies: economies of scale and scope

20:00– Outdated assumptions, Texas competition

22:00 – Rate-of-return regulation, capital bias, and technology innovation

26:30 – The changes brought by combined-cycle gas plants and digitalization

30:00 – Quarantine the monopoly, price signals

31:30 – Do conservatives still support competitive markets?

33:00 – How and why arbitrage lower prices

34:30 – Distribution system efficiency and utility incentives

37:00 – “Markets are a discovery procedure”

40:00 – Let volatility speak, Texas choices

42:00 – What’s the next frontier of competition

Resources

Guest & Company

• Knowledge Problem (Lynne’s Substack)

• Lynne Kiesling (Northwestern, Personal site, Santa Fe Institute,

Books & Articles Discussed

• The Merchant of Power: Sam Insull, Thomas Edison, and the Creation of the Modern Metropolis

• Power Loss: The Origins of Deregulation and Restructuring in the American Electric Utility System by Richard F. Hirsh

• Hayek: A Life, 1899-1950 by Caldwell and Klausinger

• Competition as a Discovery Procedure, F. A. Hayek (QJAE translation)

Related Substack Posts by Doug

•Why Are Energy Bills Rising So Fast? A Conversation with Charles Hua

• Creating a Distributed Battery Network with Zach Dell

• The Energy Capital Podcast, Episode 1 with Will McAdams

• Texas’ Load Growth Challenges and Opportunities, with Arushi Sharma Frank

Watch "The More Things Change: How the History of the Grid Can Help Us Solve Modern Challenges"

Thank you to everyone who attended my presentation and Q&A earlier this month, “The More Things Change: How the History of the Grid Can Help Us Solve Modern Challenges.” If you weren’t able to attend, or had to duck out early, I’ve embedded the recording of the presentation below for your convenience. If you enjoyed

Doug’s Platforms

• LinkedIn

• YouTube

• X (Twitter)

Transcript

Doug Lewin (00:05.356)

Welcome to the Energy Capital Podcast. I'm your host, Doug Lewin. My guest this week is Lynn Kiesling. There are few people in the electric industry I like reading and listening to more than Lynn. I'm kind of ashamed it took me this long to have her on the podcast, but better late than never. She is the director of the Institute for Regulatory Law and Economics at Northwestern University. She is a non-resident senior fellow at AEI, the American Enterprise Institute.

The reason I wanted to have her on the podcast is I think she is sort of the academic expert par excellence on markets. She really understands markets inside and out. She has been as influential talking about transactive energy, talking about distributed energy resources and how they can participate in markets. She's been talking about these things more than just about anybody, talking about them eloquently.

and really kind of pushing the envelope on what needs to happen in electric grids and electric markets for innovation. Obviously, with a focus on Texas and the electric market there, we split this into two parts. In the second part, which you'll hear next week, we got into all kinds of different stuff about data centers and their impact on electric grids, what they'll mean for competition. This was a ton of fun and a very wonky, deep conversation that I think you're going to enjoy. And more importantly,

learn a lot from. Lynn is just a fantastic teacher and it was great to spend this 90 minutes with her. So you'll have 45 minutes today, another 45 next week as we go deep into the roots of electric competition and what it means for energy transition, affordability, reliability and all of that. So with nothing further, here's Dr. Kiesling.

Doug Lewin (01:51.82)

Lynn Kiesling, welcome to the Energy Capital Podcast.

Thank you for having me, I'm glad to be here.

I love reading your articles on Substack and knowledge problem. You obviously are an economist par excellence. are doing just great work on electricity systems and the evolution of electricity systems, competition, technology. You hit on all the things. Before we get into all that though, I think it helps to kind of ground people in like the, some of the history of all this and you're, you're an economist.

but you're also a bit of a historian. So before we start talking about data centers and DRs and electric vehicles and all these cool technologies, you've written a lot, and I think just really eloquently and clearly, and I think you've done a great public service with that, about how the system of regulation we have, which is now well over 100 years old, is kind of showing some of the signs of its age. And is it quite keeping up with the technology and maybe needs to evolve?

So can you talk a little bit about where we came from, sort of how we got that system, what defines that system, and where it's just kind of not fitting with where we're at right now?

Lynne Kiesling (03:06.52)

Well, thank you. I appreciate that. And I like the metaphor, you know, feeling like as I get older, my joints are creakier. And I think that's true about our institutional framework. Yeah. It's not just bodies. It's, know, the, kind of organic metaphor is relevant here. And for folks who, and especially maybe for students who are thinking about career paths, you know, I'm an academic by temperament and by career choice. So.

You know, my fields in graduate school were industrial organization, because I went to graduate school to study electricity and with John Panzer at Northwestern. But then I got there and just got gripped by the love of economic history. And so I kept studying technology, but I actually worked in economic history. And then my other field is mechanism design, which is where the market design stuff comes in. So yeah, I have a love of history and

and it's been part of my professional work. This industry has, I think, some of the most fascinating history and it helps think both industry professionals, but also policymakers and regulators if they understand some of the history of the industry that they are engaged in. And it's definitely something that I get a lot of good feedback on, which we can talk about in a second. But the late 19th century,

in a lot of places, well, in Britain in particular, but in the US especially, the late 19th century is this cauldron of innovation. And we think of it as this kind of great man history of the iconic titans of Alexander Graham Bell running to the patent office so that he could patent the telephone and all of these things. And that's pretty much the dynamic between Bell and Edison, Thomas Edison was in all of these different technologies.

It's like the race to patent, race to patent. And so you get this really vibrant, rivalrous innovation. And at the same time, you get these iconic approaches to innovation and how innovation should proceed and what the goal should be. And so Edison in particular was really committed to number one, developing electric lighting as a commercial service and as an engineered system. And number two,

Lynne Kiesling (05:31.714)

developing it as an integrated system. And so, you know, some people today when they're sort of snarking about the lack of innovation in regulated utilities, they will say, well, you if Thomas Edison came back today, he'd recognize the system we have. And, you know, yeah, I guess that's true in kind of a snarky way, but in a really profound and meaningful sense, he envisioned the design of power systems as

fully integrated systems where you put the fuel in the generator all the way through to Edison Electric owning the lighting fixtures in your home, in his first customer's home, which was JP Morgan. JP Morgan, right. And so that integrated system from a systems theory and an engineering perspective, Edison really brought that to the party. We've had the path dependence from that. has shaped the business model. It has shaped how we've designed regulation.

And it was a success. One of the folks who worked for Edison was Sam Insull, who he sent to Chicago or, well, Sam took himself off to Chicago and said, I'm going to turn Edison Electric into something big in Chicago. And he famously interacted with the progressive era, the formers of the time, because the way power systems were getting built in cities was through getting a franchise from the city council.

It was kind of notoriously corrupt. And so the progressive era reformers said, well, we have to counter this corruption. And this is the big is bad, trust-busting era. And so they countered this and said, well, we need to municipalize all these. These should be public utilities, publicly owned. And Edison and Insull and this growing investor-owned utility industry thought differently.

And he gave this famous National Electric Lighting Association speech, I think in 1898, where he basically says, the private investor owned electric utilities, we should accept regulation so we don't get municipalized. But the other thing that I think a lot of people don't think about when they think about this era is that the investor owned utilities really benefited from regulation.

Lynne Kiesling (07:55.95)

because it got them out of having to pay a lot for their debt service. Because how do you get a consolidated Edison in New York or a Commonwealth Edison in Chicago? You buy out all your competitors. And turn of the century, in Chicago, there were like 34 competing electric utilities and all the wires. And when you have that cost structure with economies of scale, there's no way all 34 of those companies are going to be able to hang in that industry.

And so someone's going to go bankrupt. Who's going to buy them up? It's going to be Sam Insull and fire sale prices. And that's how you get this. So they were insulating themselves from having to pay more to get more debt to buy up their competitors, while also insulating themselves from expropriation from those who want to municipalize them. So that kind of foundation is important.

Yeah, Insull is one of my absolute favorites because he's such a fascinating, first of all, historical character, the whole arc of his career coming over as a young man from the UK and becoming Edison's right hand man. Like literally in the first day off the boat, Edison recognizes this guy has a mind for organization. And Edison was that like stereotypical like absent-minded genius. Like his business affairs were a mess. Insull got all that organized, works for him for decades. Does really well.

has like huge opportunities to make way more money, but goes to Chicago and is like, I'm betting on myself and builds this into this huge massive empire, which then all collapses in the depression. He dies penniless in the subway. So like that's the 62nd version. There's so much detail in there that is so fascinating. But one of those is the way he kind of broke those franchises with the, with Chicago city council, which, know, like they were not just gonna let him.

come in and do his thing, they were trying to strong arm him out. And when they tried to strong arm him out, he went out and bought up all the patents for all the equipment. And then it was like, hey guys, you want to give me a franchise now? Just total baller stuff. Like it's really wild to read about. But I think the main point for this conversation, right, is that monopoly utility business model that he made a speech about in 1898 and I think was able to...

Doug Lewin (10:16.974)

with ex-suit in 1907 somewhere right around there or something like that in Illinois. And then like wildfire right over the next six, seven, eight years, like basically every state in the US or something like 44 or 45 states, something like that within a period of seven, eight years had done the same thing. And you have this monopoly business model. So is it fair to say, I was gonna state this, but I'm gonna ask it as a question, because I'm actually really curious what your answer is. If you have a different perspective, I truly would love it, because I really...

admire the depth of your intellect on this stuff. I usually say that that was the right business model for the time because of exactly kind of just what you said, right? Like to not have a super high cost of debt, you want to be attractive to capital markets. Well, if you have a monopoly, that's pretty attractive thing. And the whole point in the 1910s, 20s, 30s, all the way through 50s and 60s, because people forget, I had Rick Perry on the podcast once and he said,

when he was born in the late 1940s, early 1950s, they didn't have electricity at his house. Like people forget this, but like it took a long time to electrify. So you want to attract capital. Was that the right system for the time? And then I think more to the point, like why does it not fit today? In what ways does it fit? And in what ways does it not?

Oh, I love that. Yeah. And Insul, there are some ways that I think Insul has really got dealt the bad hand of history. His bankruptcy, the whole 1930s New Deal, the holding companies. I think Insul's very underappreciated. So I agree with you on that. And to his credit, I will say the kind of big progressive era movements, right? The Sherman Antitrust Act and the Grange movement and all of this, you know, big is bad, robber baron.

rhetoric. It does paint this picture that these companies are rapacious and just in it for what they can get. And they forget that economics is about exchange and exchange is really about mutually beneficial cooperation. know, give me that which I want, you shall have this which you want. Right? That Adam Smith, you know, if I'm going to succeed in making a living by selling something to you, I have to get in your mind and think about what you want.

Lynne Kiesling (12:34.08)

And Insull was really good at that in addition to his tactics about patents and intellectual property. And he flat out said throughout his entire time, we want to grow by enabling universal electrification. And if we price electricity too high, that's not going to happen. And so we want to make electricity affordable for everyone so that everyone will have electricity. And there is an embedded assumption in there about

price elasticity of demand. But over time, we have evidence that the price elasticity of demand for electricity is pretty low. And so really, the way to make the most revenue is by having a higher price. So it's not clear that he got his elasticity estimates right.

Well, wait, I want to double click on that one. So like in the early days, right? What Insull did was he, and he was starting to figure this out when he was working with Edison, but he really brought it to fruition in Chicago. He came in, I think with this very much in mind when he started in Chicago. We'll say you got all these fixed costs, right? And like that time, right? The peak on the system was when the sun went down, cause was like, it was all lighting pretty much, right? And so you have this system that like could accommodate.

power demand 24 hours a day, but it's pretty much being used two or three or four hours, sun goes down and people are sitting around talking or reading their books or whatever, and they don't have to burn kerosene indoors and all that kind of stuff. But then he starts going to the factories, the traction companies, like the electric trolley companies and all that stuff. Yeah, and saying, hey, how would you like power for less than what it costs to...

The Chicago Transit Authority.

Doug Lewin (14:19.854)

maintain the horses that are pulling the trolleys, or less than what it costs to burn the coal on site at your factory, or whatever the thing was. I mean, that was like the early days of industrial rates, right? I mean, it was just like it was a system utilization thing. So maybe it's not the same as elasticity of demand, but it's related, right?

Exactly. And you are getting to one of the things that was really genius. And I will say the commercial and the engineering development of power systems was far ahead of the actual economics, right? The economics came, you know, a decade, 15 years later. Insole, first of all, he's definitely gutsy. You know, he sends a telegraph, I assume, to GE in New York and says, Hey, I want to build an enormous coal-fired power plant.

what was outside of Chicago and is now Pilsen neighborhood in Chicago. And I want it to be this big. Can you build me a generator for that? And the engineers at GE are like, dude, there's no way we could build anything that big. And he's like, come on, you're engineers. You could do this. And so then they do. And they build Fisk power plant, which was at the time the largest power plant ever built. And so he's out there with these really gutsy moves. one of them is the, go into the traction company and go into the Chicago Transit Authority and saying,

I hear you guys are talking about electrifying and building your own generation, which was pretty common at the time for urban railways to do. Rather than you incurring that cost, just buy from me and I'll cut you a deal. And so these two moves, right, building FISC and electrifying the CTA, illustrate the two conceptual pillars of the economics.

Because the theory that underlies regulation is called natural monopoly theory. And the two pillars are economies of scale, right? Build that massive honkin power plant and keep it running as much as you can given maintenance and whatever. And that just drives down the average cost per unit. There's your economies of scale. Economies of scope is the other pillar. And that's where you use a set of assets to produce two different products and that the combined

Lynne Kiesling (16:35.502)

cost of producing those two from that set of assets is lower than the cost of producing one with one set and the cost of producing the other with another set. so economies of scale and scope put the two together. You know, got your chocolate, you got your peanut butter, and that's your natural monopoly right there. And to your question, it certainly was the right business model given the technology. And I think

A lot of business models and technologies and regulations are co-determined, right? And so there's a historical determinism to the path that we end up on. And so I think given the way that technology developed, it was useful. And as you say, through the 1940s, 50s, and then plateauing in the 1960s, there's a great book. Have you read Richard Hirsch's book, Power Loss? Yeah. I'm full of book recommendations for everyone.

No.

I love it. I love that. Yeah, that's great.

But the first recommendation I always make to everyone is Richard Hirsch. He's a historian of technology at Virginia Tech. I think he's emeritus now. And this book is Power Loss. And he has really good data on essentially how the power systems hit a technological plateau in the 1960s. And then you get the weirdness of nuclear. And what he's doing is he's building the backstory to why PURPA was passed in 1978, know, with all the oil crisis and everything in the 70s.

Lynne Kiesling (18:01.708)

and then the impetus for restructuring in the 1990s. And so if you're interested in why we end up restructuring, he's your man.

Okay, definitely. I will read that. Anything you recommend. I should be careful because I know you got a lot of books. It may take me a while. All right. So you wrote a great piece called The Invisible Price Tag of Yesterday's Regulation, about exactly all of this. And I'll just read a little bit from it. Early 20th century regulation was built for a capital intensive centralized grid designed for universal service and exploiting economies of scale and scope. Three outdated regulatory assumptions now hinder innovation. So this is where kind of we're getting into like

where it doesn't quite fit. So whether or not it was right for the time, we could talk for endless, infinite amounts of time about that. But I think it would be inarguable that it at least did what it needed to do in the sense that we were electrified. mean, the United States with a few rare Native American reservations of colonias in South Texas, there's still some places that it's still problematic, but like 99 % or even 99.5%, right?

electrified, it kind of did what it was supposed to do. Of course, you could talk about co-ops and TVA and LCRA and all that as there's public power as part of that discussion too. But now we're in an era where the utility business model of spend a dollar, earn 10 % or 12 % or whatever it is, this, what you call embedded asset bias, that there is a bias to spend more.

Again, in the early days, really useful because you needed a whole lot of capital spending and you needed to raise that capital. Now we're in an era where like with all the data center conversations, there's certainly a whole lot of money being spent. But I think there is this question that is being begged. I'm begging people to ask this question. We have seen competition, I believe, certainly we're all products of our experience and our environments and...

Doug Lewin (20:01.836)

working within Texas for the last 20 years, I have seen firsthand how competition certainly in wholesale has worked really well. Retail, think it's a little bit more of a mixed bag, though we are seeing a lot of innovation, the base powers and the octopuses and the David energies and all these companies that are coming even like NRG, like the big legacy of Houston light and power when it was split up and then became.

Reliant like they're doing virtual power plants and offering customers different kinds of rate products for so you're seeing this innovation in the retail and I think there's this important question here as to what functions within the regulated model and I'm speaking about Texas. have monopoly transmission distribution utilities. Are there functions that they have that might make sense to actually have some form of competition even if it's some kind of

regulated, simulated competition, but something to have a price discovery as to whether or not the dollar the utility is going to spend is the most efficient dollar. I know this is something you've thought about a lot and written about a lot. So let's talk about that a little bit.

And I'm glad you used the phrase price discovery because I think that is the linchpin for all of this. know, a lot of people are like, well, why markets? You know, when we had it, everything vertically integrated, it was easy with unbundling and markets and having to worry about resource adequacy and accreditation. And this is all very complicated. Why? And the linchpin is price discovery. So starting at the capital intensive end and then moving forward.

This is a industry with rate of return regulation and rate of return regulation started as a feature has now developed some characteristics that I think are bugs. And those bugs have to do with incentives to innovate incentives for new technology adoption. And there's a lot of assumptions that go into rate of return regulation. The first is that you have economies of scale and scope. The second assumption is the vertically integrated structure.

Lynne Kiesling (22:11.278)

which for our purposes goes generation, high voltage transmission, low voltage distribution up to the meter. And I think it was the Energy Policy Act of 2005 maybe that defined the metering function as belonging to the regulated utility. Because at the time, in the early 2000s, we were having this conversation about precisely your question and

There's a lot of analogizing that goes on between telecom and electric because they're on similar trajectories from the 1880s onward, but there are differences. And so at the time we're like, well, we all have these and if the value proposition to the customer, if you go to get a mobile phone is sign it to your contract with me and you'll get a free phone. And why can't we do that with meters? And why can't we have

interoperable revenue grade meters, but that maybe is another conversation. But that decision got made by Congress that that's not going to happen. The metering function is part of the regulated footprint. So we start with this vertical integration and rate of return regulation means that the utility's revenue requirement is its operating costs plus its asset base, the capital it invests in, in order to

provide the goods and services that it does to its customers, plus a market benchmarked rate of return. So in theory, that little r, that rate of return, is just completely market benchmarked on some typical market opportunity cost of capital. Because it's meant to be, okay, I'm going to spend $100 on capital in this industry. What's the return I would get if I were to go use that $100 and invest it somewhere else?

And that benchmark is what we are supposed to be using in rate of return regulation. So in theory, it's that little R.

Doug Lewin (24:13.58)

supposed to be. Are we using it? can't. Go on. Keep going where you were going to go. Don't let me derail you. OK.

could talk about that.

Lynne Kiesling (24:20.918)

I am not the person with the evidence on that. are others who are doing work on that that I would recommend you to. So that's the theory. And it does work great if you're trying to build out a capital intensive network to electrify a large country. That's the right set of incentives. And I think we did succeed. But the capital bias does have consequences when you have technological change. And I think we are really learning.

right now just how technologically contingent our regulations are. And the regulation that was designed for the asset class that we had in the 1920s, 30s, 40s is much more contingent on those assets than we thought. That iron in the ground, you go to a regulator, you say, want to build a power plant. Here's the design, here's the spec, here's the cost.

We've built a billion of these, here are the kind of transformers. And so if there's any kind of cost creep, it's going to be contained by the fact that the actual technology class has a fairly narrow scope. But now we have technological change that is qualitative in nature, is qualitatively different. And it has two categories, right? One is generation. And so not only

And this is not only renewables, right? We could talk about renewables, but we can also bracket them and put them to the side. We can leave renewables out of this discussion and it would still be relevant because the pivotal technological change was the combined cycle gas turbine in the 1980s. And what that did was it really made that economies of scale and generation much less monolithic. And so the combined cycle gas turbine makes

smaller, more nimble natural gas power plants competitive with hydro and coal and nuclear. And they have different cost structures, but they can compete because they do things differently. And if you have market rules that allow for price discovery and you see the different prices over the course of the day,

Lynne Kiesling (26:41.666)

those different assets will express their different relative values and be able to make money.

Which is by the way, Texas has like 40 to 50 gigawatts of gas combined cycle all 25 years old because when wholesale market competition happened, those rushed in because they were the dominant technology. Like that's what the market chose. Yeah.

Yep, dash to gas. so, yeah, for two decades, the wholesale supply stack in ERCOT has been really long natural gas. And then that's even before fracking, right? So before the shale revolution, the shale revolution amplifies that and then extends it to other parts of the country because of natural gas pipeline networks and fracking in other places. Like I'm from Pittsburgh, so I'm a Western Pennsylvania booster.

And so, know, Marcellus Shale has made something similar in Pennsylvania. then the second category of technological change that's been qualitatively different is digital. And so all of the digital technologies are like the connective tissue. And so we can use it within an existing utility footprint for distribution automation, right? So you put sensors in your substations and they send information back to the control room.

or sensors so that when a line goes out, you know, when a line trips, you find out and it doesn't have to be me calling you to tell you that my power is out. And then around the grid edge, digitalization enables the kinds of connectivity and interconnectivity that we've experienced with the internet and these things. So all the mobile devices having

Lynne Kiesling (28:25.822)

Interoperable technology standards and common interfaces means that, you and this is a bit of systems theory here, what used to have to be a tightly coupled integrated vertical system from generator to wires to meter, because it was all run by the same company and each piece of technology dependent on the other. But now with digitalization, we can have these common interoperable standards.

And that reduces the costs of having different parties actually own and operate the different parts of the system. Or in econ speak, this reduces transaction costs in a major way. And so this is the economic argument for why the regulated footprint should shrink to just the wires. Is that, know, generation is competitive. I mean, we see that in ERCOT and other places, but I would argue ERCOT is the better example.

You know, Texas is also the example of retail being able to be competitive if you let it. And there's a paternalism there around, do customers really understand the value proposition? And it's a really complicated system. And so we have to pay attention to that and make sure that customers do understand and that retailers create goods and services and contracts and offerings for them that they can understand and benefit from.

and that any role for regulation is going to be in the background there providing the backstox for the credit checks, the anti-fraud, the consumer protection stuff. So that's my argument too in my favorite phrase, quarantine the monopoly. That the economies of scale and scope are still in the wires and the wires have the network economics aspects as well.

I want to talk about that more. So quarantine the monopoly is an interesting phrase and I think you've described it well. Just to kind of like summarize, you basically like, because monopolies don't have that price discovery aspect to it, there isn't market competition. There isn't the ability to say, we're going to spend this $1 here. Let's figure out if there's

Doug Lewin (30:43.702)

a way to do it for 50 cents or 75 cents or 90 cents or whatever. You could do that on the generation side. You had this great quote in your piece called Markets as Minds where you quoted Friedrich Hayek as describing prices as a system of telecommunications, which I find really... Have you read the new Hayek biography, the one that just came out a year or two ago? I bought it the other day and it arrived and it's like a thousand pages and I'm really intimidated. I do want to get to it.

but maybe I'll let you read it first and you can. Probably, it's like out just in the last year or two.

Tell me.

Lynne Kiesling (31:18.946)

Yeah, even better, that's volume one. And it only goes up to like 1960.

I really want to understand Hayek, I don't know if I could commit to a multi volume. Okay. Well, stay tuned, dear listener.

I'm not just saying this because Bruce Caldwell is a friend of mine, but it is very well written. And if you are interested, and I generally don't read biography, but really well written biography that tells you something about the social and economic and the political history of the time, as well as telling you about the person.

Yeah, I am really fascinated by that because the book he's most known for, right, is Road to Serfdom, right? And it's this whole, like, I think there's a really fascinating thing right now in conservatism, right? That like, because he's one of the founders of conservatism, and it was this like very anti-authoritarian and free market thing kind of mixed together. And we're in a weird time where I can't really tell if conservatives still believe in that or not. I don't know.

Yeah, that doesn't really map anymore. And I mean, he's got this famous essay and is, think, actually at the back of Constitutional Liberty, which he wrote in 1960, this famous essay called Why I Am Not a Conservative. Oh, wow. And so it's interesting and it's still contested, right? Because does he mean he's not a conservative in the European, you know, like the German historicist sense or in the American sense, which is more kind of British wig historically? And so the political theorists will still

Lynne Kiesling (32:54.176)

have conversations about this. But yeah, if you're interested in those kind of questions.

We should talk. I will read it eventually. I've got a long stack of books. I'm more ambitious in my book buying than I am realistic. it's okay. Ambition's not a bad thing. So Hayek describes prices as a system of telecommunications. So we have that right now, right? In Texas, particularly in the wholesale market, in the retail market, there is this very intense right now on a day-to-day basis, right? Anytime you open up

the ERCOT app or just go to ERCOT.com and look at the dashboard. You could see the prices on there. When there's a very intense communication going on and people trying to figure things out, know, it really struck me. You know, you get these moments where, and I'm very sympathetic to legislators, particularly in Texas, where they're part-time legislators, they're paid $600 a month, they've all got other jobs or they're retired in some cases, but most of them are working other jobs. They've got a thousand different issues they're dealing with. So I'm sympathetic.

But there was this whole discussion around arbitrage in the market and they made it sound like it was the worst, most evil thing. The legislators were like, you mean that they're like buying low and selling high, like you're, you know, selling at higher prices when they're buying it lower and like, and I understand that instinct cause it does sound bad, but you have this great core. say every act of arbitrage flattens price volatility, reshaping tomorrow's market conditions and incentives. Right? So we've seen this in Texas where

Two summers ago, and even last summer, a lot of days of really high prices, signals to build more particularly storage, but a lot of gas, not a lot, some gas peekers and a whole lot more entering the queue. Our queue for gas peekers is 150 % larger than it was one year ago. And that's because of this system of telecommunications. There is literally a signal that is coming through the noise to generators that like.

Doug Lewin (34:47.938)

hey, these prices are high. Well, now they're lower. So now there's another signal and you have this kind of give and take that is happening there. I want to hear your thoughts on all of that and for you to explain more about why arbitrage is actually a good thing and all those things. Where I was going with this though is we don't yet have that on the poles and wires side of things, particularly on the distribution side of things. And there are examples, you wrote about an example in New York.

I can't remember exactly, maybe you can describe it. was a while ago you wrote about it, but it's top of mind for you. But it's something along the lines of like, I think it was Con Ed got some kind of performance incentive bonus for actually integrating DERs into their systems such that they were spending less money. So the regulator says, you're going to need to spend, and I'm making up numbers isn't the actual example, but you're going to need to spend like $50 million on this set of upgrades in the distribution system.

But if you go out and find that there's EV managed charging and storage in people's garages and energy efficiency and all of these things that can be done, and you wouldn't need to spend that 50 million, you could provide incentives to customers which lower their bills. And then it only costs just picking a number 25 million. So it's like half as much. So even the non-participants are benefiting from that. Then we would give the utility a bonus on that of whatever the number is, five million, seven million.

Still, the total of that 25 million spent on the distributed energy resources plus their incentive would be far less than what they would have spent on that infrastructure. But where we are right now in Texas and I think in the vast majority of places is that system of telecommunications doesn't exist. We can't discover if there's an alternative to that $50 million, so we just spend the $50 million.

I think that's exactly right. And you've got so many things going on in my head.

Doug Lewin (36:38.016)

A lot of plates spinning in the air right now.

lot of plays. So the price discovery and one of the ongoing conversations that we have in electricity economics, energy policy regulation is around these questions of market design. And I think that we've got a lot of evidence showing that the move to wholesale power markets has been beneficial for consumers, generated a lot of consumer surplus.

generated a lot of producer surplus, right? There's been profits. Although, as with anything else, with that dash to gas, right, the marginal return on the next additional investment in a gas turbine is going to get lower and lower the more and more of them you have. And so you had bankruptcies as well. But that's one of the features of markets. Sure. Not a bug, a feature, is that people risk their own capital and not rate payer capital.

Bingo.

to figure out what the right amount. And of course, you're never gonna know that in advance, right? Markets are a discovery process. Well, discovery procedure is Hayek's exact language, but markets are a discovery procedure and you figure things out and it's trial and error because the world is very dynamic and systems are very complex. And so trial and error and risking your own capital is how we have the best potential for flourishing.

Lynne Kiesling (38:04.238)

And of course, there are institutional design details that matter around consumer protection and fraud and all of that. But high-level broad brushstroke, know, Marcus says discovery procedure are really important. But that's one reason why I think an important piece of the conversation we have, a little less so in ERCOT, but much more so in the other RTOs, is about price fidelity. The only way this really shows up in ERCOT is

that we have these federal production and investment tax credits for wind and solar, the PTC and the ITC. And of course, those are slated to sunset fairly aggressively. So we'll be doing the experiment to see just how much of an impact.

Any predictions, Lin?

No, I'm not. I'm with Yogi Berra. Predictions are really hard, especially

about the future. Yeah, no, I get you. You're too smart for that.

Lynne Kiesling (39:01.646)

But in like PJM, for example, a few years ago, you know, they had this enormous controversy because some of the states in the PJM market were implementing renewable portfolio standards and implementing state policies that were favorable to wind and solar. And that was having distortionary effects in wholesale price formation. And so

The PJM put in this maximum offer price rule, MOPR, which was very unpopular and very poorly designed, and they've repealed it. But it does reveal an important fundamental truth, which is the fidelity of that pricing system, that telecommunication system, those price signals, is really important. And so we should figure out ways to implement our policy objectives that don't interfere with prices.

Yes.

Doug Lewin (39:55.758)

Well, and you wrote about that in that same Markets as Mine piece, where you had a lesson for regulators, and the number one lesson you had on there was let volatility speak. Price spikes are not market failures. They're distress signals that mobilize flexible resources. And it's interesting because Texas really is, I I give just a ton of credit for Texas policymakers. A lot of times people say to me, it's amazing that Texas has got all these renewables and battery storage.

without the policy to support it. And I'm like, well, okay. There was a renewable portfolio standard back in 99. It was increasing to five. it was satisfied a long, long time ago. think by 2010, we'd reached it. But it is a policy choice to have a market. It is a policy choice to have a market that has a very high price cap. That is a policy decision. And I think it's the right one because it does...

Like you said, it puts the investor dollar at risk instead of putting all that burden on the rate payer. And I do believe that is one of the reasons we have lower costs here is because that price discovery continues to happen and that volatility has been allowed to work. It certainly hasn't been smooth, right? There's lots of times where that gets called into question, but I think time and again, it has proven itself and then prices drop real low.

and then investment starts to slow and then they get high again. It's this whole process of communication. And here's one of the things that I think is most important about this and I think is high Echean and you can correct me if I'm wrong, but it's like, there is no human being that is smart enough to figure all this out. This is the fundamental flaw in central planning, right? And it's why markets work better is because as clever as we are, we're pretty clever species, none of us is...

wise enough, smart enough, has perfect information enough to say, this is the exact, I see these conversations all the time. One of the most common like Twitter comments and LinkedIn comments is, we should build more nuclear. It's like, well, do you know that? Like, have you done all the price discovery? Like in some of them, to be fair, like some people are entrepreneurs with nuclear companies and they are putting investor capital at risk and taking, and that's great. And I don't have the wisdom to say,

Doug Lewin (42:12.812)

that's a smart investment or that's a dumb investment, that's what markets are for, right? And I just think that sometimes, particularly in the systems where they're fully vertically integrated utilities, you are putting the regulator in a position where they have to be perfect and they cannot do that. That's why central planning doesn't work. So what I'm trying to figure out is what is the next evolution of competition? Thanks for tuning in to the Energy Capital Podcast.

in the cute.

Doug Lewin (42:40.204)

If you got something out of this conversation, please share the podcast with a friend, family member or colleague and subscribe to the newsletter at douglouen.com. That's where you'll find all the stories where I break down the biggest things happening in Texas energy, national energy policy, markets, technology policy. It's all there. You could also follow along at LinkedIn. You could find me there and at Twitter, Doug Luhman Energy, as well as YouTube.

Doug Lewin Energy, please follow me in all the places. Big thanks to Nathan Peeby, our producer, for making these episodes sound so crystal clear and good, and to Ari Lewin for writing the music. Until next time, please stay curious and stay engaged. Let's keep building a better energy future. Thanks for listening.