This podcast is on YouTube with Graphs

Congress’ new budget bill is an energy earthquake. It could wipe out tens of gigawatts of energy production, just as we’re experiencing load growth unlike anything since the 1960’s. It will drive power bills higher for families and factories, and give China the upper hand in the race for 21st century economic supremacy.

To understand in more detail the impacts of the federal budget bill, this week on the Energy Capital Podcast, I talked with Dan O’Brien, senior modeling analyst at Energy Innovation. His team modeled what this bill really means for Texas and the numbers should stop us in our tracks.

If you’ve been reading this newsletter, you know I’ve warned about this moment for months. Now, the data is here. It’s worse than we thought. We were on a path to energy abundance and we’re about to get energy scarcity including increased risk of blackouts and much higher electric bills.

From Ramp to Cliff: What This Bill Actually Does

Here’s what Congress passed:

Ends clean energy tax credits abruptly. No glide path, no transition, just a cliff.

Imposes impossible project timelines that most developers can’t meet.

I’ve written before about how this creates scarcity, not abundance (Energy Scarcity). We’re pulling the cheapest, fastest-growing resources off the table while demand is surging. That’s a recipe for higher prices and weaker reliability.

And make no mistake: this isn’t happening in a vacuum. It’s happening right when Texas has proven that solar and storage are great for reliability and affordability.

The Modeling: 77 GW Gone

Dan’s modeling tells the story:

77 gigawatts of lost clean energy in Texas, including over 50 gigawatts of solar and over 20 gigawatts of wind)

Only 2 gigawatts of additional gas

Household power bills up $400–$500 a year

Industrial energy costs up 50%

Tens of billions in lost rural tax revenue

Put that in perspective: ERCOT’s entire summer peak is about 85 gigawatts. This bill wipes out nearly that much future clean power before it’s even built.

These numbers aren’t isolated. Princeton’s REPEAT Project and Columbia’s Climate Knowledge Initiative show the same trend: abruptly ending credits doesn’t save money. It costs money—because you’re replacing cheap renewables with expensive alternatives, or worse, with nothing at all.

Demand Is Exploding, So Why Are We Pulling Back?

At the same time, Texas demand is skyrocketing. From 2021 to 2025, Texas has experience 6% year-over-year growth, the fastest since the 1960s. AI data centers, crypto, and industrial electrification are all plugging in at once.

And here’s the kicker: the resources meeting that demand surge aren’t gas or coal. They’re wind, solar, and batteries. They’re 92% of what’s been added since 2021. In the first half of 2025, wind and solar made up 40% of ERCOT’s generation mix. Batteries are breaking records almost monthly, keeping the grid balanced during extreme heat and sudden shifts.

ERCOT calculated summer energy emergency risk dropped from 16% to under 1% in one year, because of solar and storage. We have the data. We have the results. So why are we sabotaging it?

The Human Side: Jobs and Rural Texas

The energy sector is one of the largest drivers of job growth in Texas. These are real people—60,000 Texans working in wind, solar, and storage, including 6,000 veterans. It’s rural school districts balancing their budgets with wind and solar tax base and farmers and ranchers keeping their land in their families for another generation.

It’s welders, electricians, and manufacturers in counties that haven’t seen this level of investment in decades.

Global Stakes: China’s Electrostate Moment

Zoom out. While we’re cutting our legs out from under us, China is sprinting ahead. Last year, they added 400 GW of clean energy, several Texases worth of power. Last month, they put in 90 gigawatts of solar. The Financial Times calls them the first “electrostate.”

The U.S.? We added 60 GW in 2024. And now we’re debating LNG power plants that don’t exist. As I wrote in Energy Submission: this isn’t energy dominance. It’s energy surrender.

If we abandon clean energy leadership now, we’re not just risking higher bills—we’re giving away the 21st century.

There’s Still Time: Ramp, Don’t Cliff

I’m not arguing for permanent subsidies. We should phase them out, but smartly, with predictability. A ramp-down avoids price shocks, keeps manufacturing momentum, and protects rural tax bases while we scale what’s next.

We’ve already proven the formula: reliability up, prices down, emissions falling. It’s not theoretical. It’s working. And throwing it away overnight isn’t policy, it’s ideology.

The Bottom Line

The Texas grid is stronger than it’s ever been, because of solar and storage. That’s not my opinion; that’s ERCOT’s own data. Reliability is improving, costs are falling, and we’re finally catching up to the energy future the rest of the world is racing toward.

This bill reverses that progress. It’s a choice between abundance and scarcity, between leadership and surrender. And the clock is ticking.

Timestamps

00:00 – Introduction

02:00 – What is the federal budget bill and why is it important?

04:30 – Impact on Texas power

07:00 – Why is there only a tiny increase in new gas capacity

10:00 – Modeling Assumptions and Safe Harbor Provisions

12:30 – Demand forecasts and modeling variables

14:00 – Residential energy cost increases: $480/year

16:00 – Why that could be worse if Treasury’s guidance is restrictive

19:00 – Why are power prices high if renewables are lowering costs?

21:00 – 54% increase in power costs for large commercial & industrial customers

25:00 – Job losses from the federal bill

29:00 – Rural community impacts and manufacturing losses

30:00 – Policymakers could revisit this policy as the impacts take hold

32:00 – Phasing out credits would protect consumers and end them permanently

Resources

Energy Innovation - Linkedin

Daniel (Dan) O’Brien - LinkedIn

Updated: Economic Impacts of the U.S. “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” Energy Provisions — Energy Innovation

Impacts of the One Big Beautiful Bill on Texas Energy Costs, Jobs & Emissions (PDF) — Energy Innovation

Texas Reliability Entity 2024 Reliability Performance & Regional Risk Assessment — Texas RE

Related: Writing

TRE: Solar and Storage Help Reliability; Texas Grid Roundup #68 - Doug Lewin

Clean Energy Development Slows Without Tax Credits — Texas Tribune

Boom Fades for U.S. Clean Energy as Trump Guts Subsidies — Reuters

What the ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ Would Mean for Renewable Energy — Governing Magazine

Transcript

Doug Lewin (00:05.922):

Welcome to the Energy Capital Podcast. I'm your host, Doug Lewin. My guest this week is Dan O'Brien, senior modeling analyst at Energy Innovation. Dan has spent a lot of time working on a model to show the impacts of the federal budget bill that passed the Senate on July 3rd, signed by the president on July 4th. This episode is a shorter one. Quick note to the listener, there were some charts and graphs. You can see all of that on the YouTube channel, Doug Lewin Energy.

But if you are listening to the podcast version, we made sure to describe all the charts and graphs so you'd be able to follow along. The stuff that we got into in this particular podcast, the change in capacity that will be coming from the federal budget bill, which was a massive loss for Texas, 77 gigawatts of capacity. In the next 10 years, we talked about which sources that comes from and what might fill the gap and what doesn't fill the gap. We don't see a whole lot of gas. So we talked about all of that. We talked about the change in cost, both for households and businesses, a massive rise for both, but much bigger for businesses, about a 20% increase for residential consumers. That's $500 per year per family, but a 50% increase compared to had current policy stayed in place for businesses. We also talked about job losses, the loss of investment impacts on rural communities.

Compare Texas to the impacts of other states. This is a short but very dense, very full episode. Hope you learned a lot from it. As always, please give a five-star review wherever you listen to your podcast. Please follow along, become a subscriber at YouTube, the channel's Doug Lewin Energy. And to subscribe to Texas Energy and Power Newsletter and the Energy Capital Podcast, go to douglewin.com. And with nothing further, let's jump in to this podcast on the impacts of the federal budget bill on Texas. Thanks for listening.

Dan O'Brien, welcome to the Energy Capital Podcast.

Dan O'Brien (02:07.694):

Thank you for having me.

Doug Lewin (02:09.389):

So let's start with you've spent a lot of time obviously modeling the federal budget bill. Let's just start from the highest level. Why? Why spend time modeling this bill? What is the bill and why is it so important that you want to spend time modeling?

Dan O'Brien (02:25.166):

Well, energy is everything, Republicans got that right in campaigning last year. And one thing that this big, beautiful bill does is really changes how energy will be produced and transformed and consumed in the US in the next decade. And this happens a few different ways. So the biggest one being changing the tax credit structure around energy in the United States. So the big bill repeals a number of different tax credits that are offered to companies to incentivize development of new energy facilities like power plants in the US. It also increases the amount of oil and gas leasing in the US through running more auctions and lowering the royalty rates for these projects. It delays conservation funding that was passed in 2022. So it's kind of all consuming and touches a number of different areas. And my organization is one that tries to focus on producing quantitative analyses of bills like this. So we've definitely put a lot of time into it and happy to chat through it.

Doug Lewin (03:34.612):

Awesome. And you guys at Energy Innovation have done a great job and a great service in modeling this. I do just want to say from the outset, there are a lot of folks out there modeling this. And one of the articles I wrote, I think it was Energy Inflation, but we'll put a link in the show notes. I cited, I think, four different modelers that had in the same ballpark of similar results. There's, of course, key differences and all of that, but so that people don't have the impression that this is kind of a lone voice out there. There's a lot of folks doing this. They're all kind of directionally showing the same thing, but for energy innovations model, let's talk about what you're actually seeing or the results in the models from the passage of the federal budget bill. Let's start with what is the change in capacity. And we're going to focus mostly here on Texas, the Energy Capital Podcast, but if you want to cite some of the national statistics, I think they're relevant, but mostly with a focus on Texas. Let's start with what do we see in the differences in what gets built with this bill in effect.

Dan O'Brien (04:35.138):

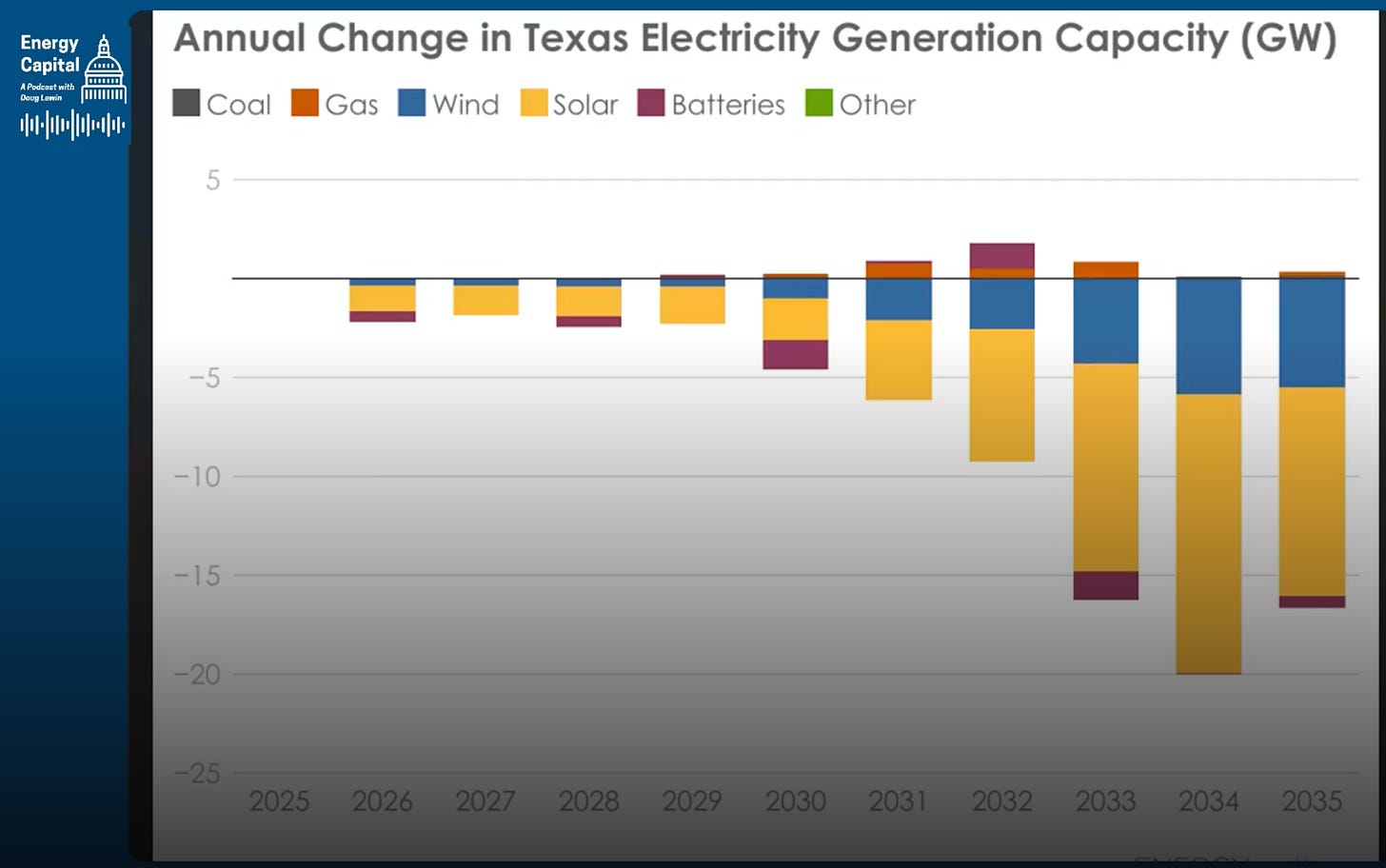

Sure. So the biggest change is this bill repeals and shortens the lifetime of the clean electricity tax credits for developers and utilities around the country. And these are tax credits that incentivize new power plants coming online. And they're especially targeted towards renewables, though they're technology neutral. So any power plant that's not generating emissions can qualify for this. And because of the timelines for development and how simple these projects can be, wind and solar tend to be the technologies that are losing out. And so what we see is those are the biggest losers in terms of new capacity in Texas. Texas is actually the state that we find has the biggest losses in terms of capacity from this bill, about 77 gigawatts of lost capacity in the next decade. And about two thirds of that is solar and one third is wind, roughly.

Doug Lewin (05:35.182):

Just to put that in context, that's obviously a huge number. Texas' all-time peak demand in the summertime is about 85,000 megawatts or 85 gigawatts. So that's almost as much as Texas' entire peak demand. The total installed capacity in Texas is somewhere around 170. So losing 77 is a great big deal. But I would like for you to address while you said there's 54 gigawatts of lost solar, 23 gigawatts of lost wind, three gigawatts of lost batteries. And then you had in your models only two and a half gigawatts of increased gas. That's certainly, I think, counterintuitive to what a lot of folks, including probably the folks that authored the bill and championed it, thought would happen. They talk a lot about how we need less renewables, we need a lot more gas. Can you talk about why you think the model produced that? Why is that the result?

Dan O'Brien (06:28.462):

Sure, and let me share a graphic here that kind of shows off that point that you're talking about.

Doug Lewin (06:33.494):

And Dan, as you're pulling that up, let me just say for, because I don't think I said this yet. We will describe these. If you're listening to the podcast audio only, we'll describe them so you won't lose anything. If you're in a place where you can follow along on YouTube, the channel is Doug Lewin Energy and we'll have the video there so you can see the graphs. Go ahead, Dan.

Dan O'Brien (06:51.758):

Sure, thank you for that. So the graph that I'm showing is the annual change in Texas's electricity generation capacity. And what it shows is that solar is the biggest loser, wind is second to that. And it shows a stacked column chart highlighting that the losses in these different technologies increase over the next decade. We see a few gigawatts lost in 2026 to 2029. But in the early 2030s is when we see the biggest losses in new capacity for these technologies. Simultaneously, it shows that there are really small additions of gas plants on the positive end of the chart. As Doug pointed out, about 2 and 1 half gigawatts of new gas capacity is what we project to come from the bill. Now, why is that? Folks who are listening here may be well-tuned to the shortage of new gas turbines that utilities and developers are unable to source new gas turbines for plants that they might want to build in the next four or five years. So we don't really have the ability to meet the loss in renewables with a gain in new gas plants. And as a result, what we're really seeing is existing gas plants, especially, are just running longer hours of the day to meet existing demand and growing demand due to things like data centers and manufacturing facilities.

Doug Lewin (08:20.874):

We would see... Your modeling is showing an increase in capacity factor of gas plants, which are probably... I think the number is 45, 50% right now. They might go to something like 60, 70%, something like that. They're higher.

Dan O'Brien (08:36.994):

Yeah, that's exactly right. So presently we see around 40 to 50% capacity factor for gas plants, that is for combined cycle plants. And what we find in our modeling is that these tax credits for renewables in the 2030s especially really drive down that capacity factor. As more and more renewables are hitting the grid, we're seeing those more efficient combined cycle plants are running fewer hours of the year down into like the 30s percents range. But as a result of the bill, the trend reverses and those plants are running more hours into the 50s and 60% range. So it's really a dichotomy of whether or not these tax credits are in place that are really increasing the profitability of new wind and solar plants to meet rising demand.

Doug Lewin (09:27.862):

Now, there's obviously something interesting that's happening that is probably really hard. I would imagine is really hard to model. You could let me know if that's true or not. You're modeling the final bill, which the Senate modified to allow a runway for wind and solar projects and other projects as far as the foreign entities are concerned. But basically you have through the end of the year to commence construction, as long as you're completed in four years, you can still get the tax credit. Are you modeling that or are you adjusting to what appears to be the executive order from the president to treasury, which is basically trying to obstruct that and make commenced construction a much harder definition? Are you able to account for that in the model? Are you just modeling it sort of on face value as it passed the Senate and was signed into law?

Dan O'Brien (10:18.914):

You know, all these groups, you noted at least four groups modeling this. All of us are doing our best at interpreting what we think will come out of this. We are assuming that some producers are able to pull forward their construction dates and begin construction this year so that they can engage with the safe harbor rules and claim the tax credits for the next few years. Really intricate ways of doing that. Essentially what we assume is the Energy Information Administration has a list of planned power plants. And we assume that all those plants that have received regulatory approval but have not yet started construction can pull forward that construction date. I think it threads the needle relatively well, especially given the executive order kind of aims to make it harder for plants to receive that regulatory approval and start construction. So maybe we're a little bit conservative in which producers and developers are able to do that. But if anybody tells you they know the future right now, they're not telling the truth, you know.

Doug Lewin (11:23.502):

No, anybody ever tells you they know their future, they're not telling you the truth, but especially now, there's a lot of uncertainty. And I think unfortunately, the administration's point is to have a lot of uncertainty, which is unfortunate. But it's safe to say, Dan, that what you just showed in that chart, which is a lot of drop off in the 2030s and only a little bit in the late 2020s, could be much worse. We could see more supply constraints, higher prices, all that kind of stuff. If the guidance out of treasury is particularly onerous, this could actually be worse.

Dan O'Brien (11:58.018):

Yes, it could be worse, the degree to which is really hard to estimate from a quantitative approach.

Doug Lewin (12:03.854):

Got it. Okay. Thanks for that. Before we get into talking about cost, I do want to just ask you kind of a modeling question. What are you guys putting in there for demand, especially in the ERCOT market? Because there's such a wide range of demand forecasts. I had Olivier Bofisse from Aurora Energy Research on the podcast, and their demand forecasts in the 2030s are in the low hundreds at 110 gigawatts. ERCOT's are 150 by 2031. There are some that are forecasting much, much higher even by the early 2030s in a 200 range. So obviously within that spread, that's going to create very different results. So where do you guys kind of come out on the demand side of the equation?

Dan O'Brien (12:48.098):

Yeah, I don't have a number to put in front of you right now, but my guess is somewhere in the middle there. For most of our demand forecasts, we'll pull government data, so EIA data, for example, so wherever they're landing. And then we're starting to build into the model a little bit more exogenous demand projections so we can better account for data centers and growing demand from that because the government projections can be a little bit delayed and trying to stay on top of growing demand from that side is something we're focused on.

Doug Lewin (13:18.584):

Okay, cool. Yeah, it'd be great if you can, we can include in the show notes. I'd love to have what that is. Because I do think part of what is going on here is, and one of the reasons why this is so difficult, is these things play on each other, right? If there's not as much supply, particularly affordable supply, then you may end up getting less demand, right? But if that demand pool ends up being really strong, you could get a lot more supply, but it's going to end up being very high cost supply. So it's obviously really hard, but I think that number will matter a lot and how that's modeled if there's a different range. I think having different demand numbers is a really useful thing for folks in the market and planners, regulators, policymakers, for everybody to be able to see.

Dan O'Brien (14:05.974):

Yeah, completely agree.

Doug Lewin (14:08.022):

All right, cool. So let's talk about cost. So this is one of the main takeaways you guys have. Again, you modeled all 50 states. Texas was one of them that came out worst. What did you see as far as increased energy costs? Maybe we start with households, but you can take it in whatever order you want.

Dan O'Brien (14:25.934):

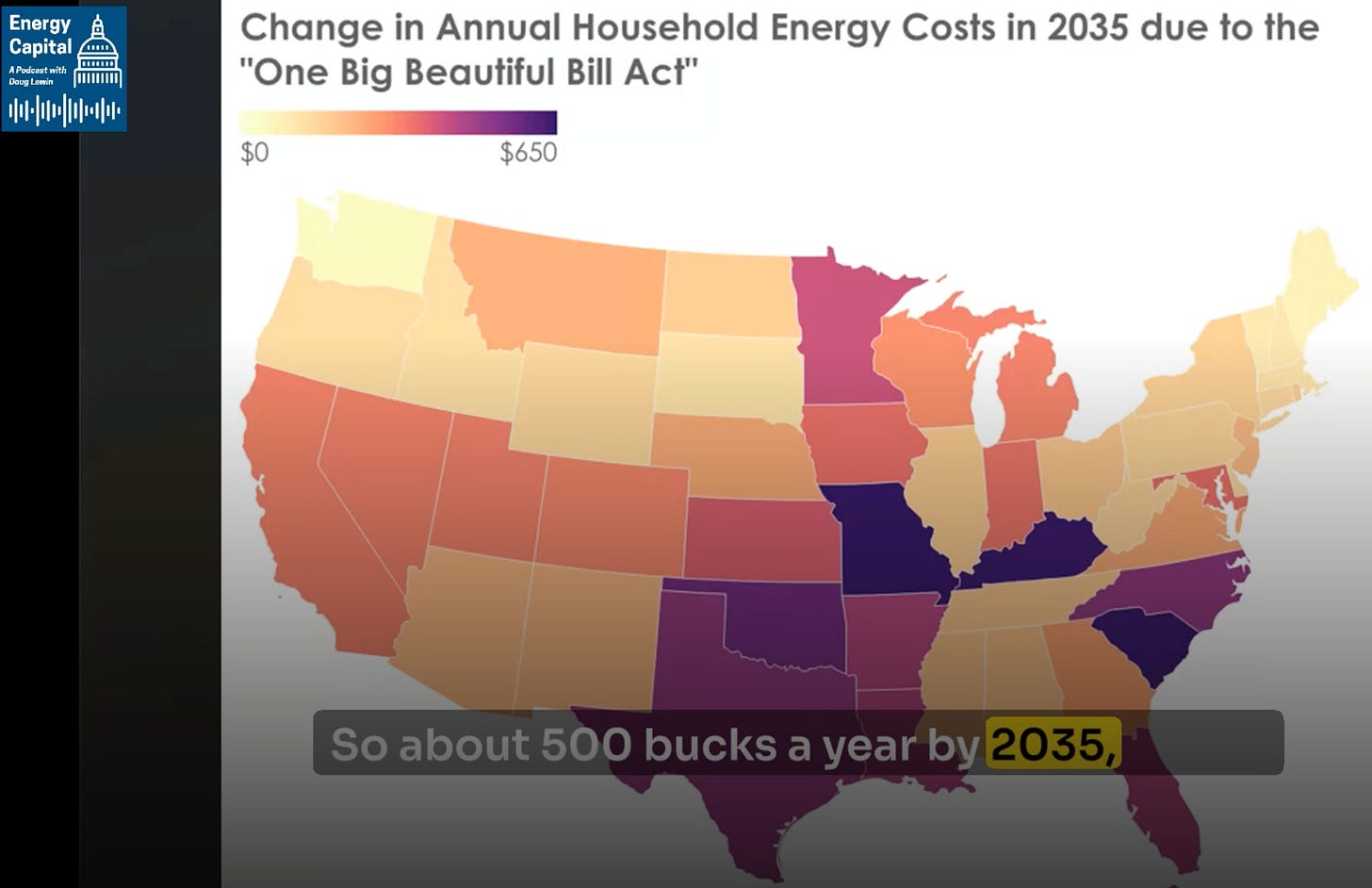

Sure. So I feel like just starting with overall power prices is helpful. When you pull renewables offline or don't add them to the grid, what you see is gas running a lot more often like we just discussed. And when you see that across the whole country, we find that the incremental gas demand from the bill outweighs the incremental gas production from the bill. And just from like a supply demand perspective, that shows you gas prices going up. So you pair that with increased reliance on natural gas and you see power prices go up. And that's something on the order in Texas of around 20 to 50% depending on the consumer. So residential consumers probably on the lower end of that and then industrial commercial consumers on the higher end. So what does that mean for households? In Texas, what we find is around $480 a year of increased energy spending. And where does that fit? So depending on the state, we see somewhere between $50 and $650 of increased energy spending.

And I'll put a graphic up on the screen here that can kind of show where those costs are distributed. So what we find is it's really states in the South and the Midwest that have the highest increases in power. And these are states where, you know, they're really well geographically oriented for renewables. You know, the sun shines a lot in the south and the wind blows a lot in the Midwest. So when you pair that with tax incentives, it makes a really economically favorable environment for renewables. When you pull those back and a lot of these are states that don't have strict renewable portfolio standards, for example, that are maintaining that market certainty and giving business certainty to developers. And so those are the states where power prices tend to go up the most.

Doug Lewin (16:25.806):

So about 500 bucks a year by 2035, a little over $200, $220 by 2030. I mean, again, I just want to emphasize the degree to which those power prices might shoot up quicker will depend on a lot of how this plays out at treasury and what that guidance is. If it's very restrictive, I think we're going to see power prices that you'll pull forward those price increases. Is that a fair conjecture to make?

Dan O'Brien (16:56.322):

Yeah, that's absolutely right. So by assuming that producers can pull forward the construction date on some power plants, we're assuming that some of those renewables get online in the near term and keep prices down in the near term. But if the treasury guidance reverses the ability of those developers to do so, then power prices will go up more in the near term.

Doug Lewin (17:16.811):

If you're listening and not able to see the map, what we're looking at on the map is sort of a line right up the center of the country with some of the biggest price increases, including Missouri and Kentucky, but also Kansas, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Iowa, Minnesota. Like Dan said, a lot of the windiest places. Then as far as sunny places, you're seeing high increases in North Carolina, Florida, Texas. The states that fare worst are Missouri, Kentucky, South Carolina, Oklahoma, Texas, kind of right there in that next tier. You said that's about a 20% increase, the $500 equates to about 20%.

Dan O'Brien (17:50.358):

In residential power prices. Exactly right.

Doug Lewin (17:53.048):

For residential power prices. Okay, great. Let's talk about, well, not great, it's terrible, but great information. Let's talk about what this means because there's huge implications here for the broader economy. Obviously, it's always important to center this around people and always important to ground ourselves in the fact that there is a large portion of the public that is unable to afford their energy bills as they are now. So the stat that I like to cite there is that one out of six people nationally are in arrears on their electric or gas bills or both. The U.S. Census Bureau consistently shows 30%, sometimes higher, sometimes a little lower, but usually not much lower, about 30% that self-report choosing between paying for energy, their light bill, or medicine and food. So that's a very devastating increase to residential. I hear a lot and Dan, you're happy for you to talk about this if you like, but I feel the need to address this because I get this a lot. People are like, look, power prices are already high. I don't know what you're talking about. I'm hurting. My bill's really high. You know, I get this a lot. And what I like to remind people, first of all, I hear you. I get it. It's painful and it's not right.

We should be doing more to help people. I'll acknowledge that first and foremost. And your power prices would be a lot higher right now if we didn't have renewables in the mix like we do. They do put a downward pressure on generation. Most of the increase in the last few years has come from transmission and distribution and specifically really the distribution side of the grid. So we've seen large increases in T and D. Now we're going to see large increases in generation too. So it's kind of this double whammy. You're welcome to address any of that you want. I do also want to talk about the commercial sector and industrial consumers because this is a lot of the drivers of the economy and if power prices go up there, particularly for those that are very price sensitive, which would include steel mills, oil and gas producers that are trying to connect to the grid, refineries and petrochemical facilities, all kinds of different industries that are very price sensitive. So feel free, Dan, to address anything I just said as far as affordability and all that. And then let's do talk about commercial and industrial.

Dan O'Brien (20:13.518):

Sure. So I appreciate your point that it is important to both say energy costs are too high and are impoverishing people and renewables are helping. I'd point to a report from Josh Rhodes that found about $32 billion of cumulative savings thanks to renewables in ERCOT. And that was between 2010 and 2022, I believe. So renewables help people. It's really hard to see that impact because all you see is your own power bill. You don't see here's your power bill and here's what it would have been if we didn't have these power plants on the grid. That's right. So I think that's really helpful perspective and important one for folks in energy to focus on. To your point, residential consumers, households, people like you and me, we don't just pay for a gas turbine to run. We pay for all of the services that go into making sure our electricity is reliable and it doesn't shut off at random parts of the day. We pay for the transmission that gets it from the power plant to our towns and we pay for the distribution that gets it into our homes. That's one reason that we find that 20-ish percent increase in residential power price being lower than the 50-ish percent increase in power price for commercial or industrial consumers.

Doug Lewin (21:38.964):

I just got a pause. Wait, 50% increase for large consumers specifically in Texas.

Dan O'Brien (21:46.478):

That's right. 54% is what we found.

Doug Lewin (21:51.146):

Yeah, keep talking, tell me more, because that is an eye-popping figure.

Dan O'Brien (21:56.586):

It's an eye popping figure. And what does it mean for business is kind of the key question here, right? There are a lot of industries that are heavily reliant on costs of energy. So data centers, for example, we keep hearing about them, hearing about the boom of AI, but a majority of the operational costs for a data center are power. Most of the spending that they do on a day-to-day basis once they've opened is paying for electricity. And so if you see the price of power increase by 50% in your state, you're not going to be a state that's attracting new data centers. Other types of consumers like steel mills, for example, you listed, or other manufacturing sites that are heavily dependent on electricity are going to find themselves going to other states. These companies are going to other states that have lower power prices or going outside of the US and offshoring to places where there is this continued investment in the technologies of the future on the grid that are making electricity cheaper rather than subsidizing the past.

Doug Lewin (23:09.857):

54%. So the average megawatt hour in ERCOT the last couple years from memory is something like 35, 40 bucks, not including 2022 where gas prices were so much higher, but say 23, 24 even this year were somewhere around 30, 40. So you're talking about going to like $60 a megawatt hour on a wholesale basis, something like that.

Dan O'Brien (23:31.822):

I think an important clarification here is we're not comparing to today's numbers. We are comparing a world before the bill and a world after the bill.

Doug Lewin (23:41.368):

Good distinction. Okay.

Dan O'Brien (23:43.822):

Yeah. So a world before the bill, renewables make up a large share of the grid, and they're running in more hours of the day, and they're producing electricity without any fuel costs. Then you shift to a world where we're heavily dependent on gas, and gas prices simultaneously are skyrocketing. And so the difference between those two scenarios is a 50% increase in power prices for industrial consumers.

Doug Lewin (24:11.16):

Got it. How does that compare to other states? You talked about how different data centers or any number of industrial customers might move to other states. Are other states seeing 50% increase or is that really kind of unique to Texas?

Dan O'Brien (24:26.574):

Texas is towards the top of the list. There are a few states that are higher. Kentucky, for example, like you listed earlier, Kansas, could be heavily reliant on wind, but without the tax credits, kind of shifts back to coal or gas. Oklahoma sees really high increases. Again, similar, really favorable environment for wind, but without the tax credits is more reliant on fossils. That said, aside from those few states, Texas is definitely seeing amongst the highest cost increases and definitely higher than a lot of states, especially in the Northeast where you have renewable portfolio standards and other state level policies giving a little more economic certainty to renewable developers.

Doug Lewin (25:09.314):

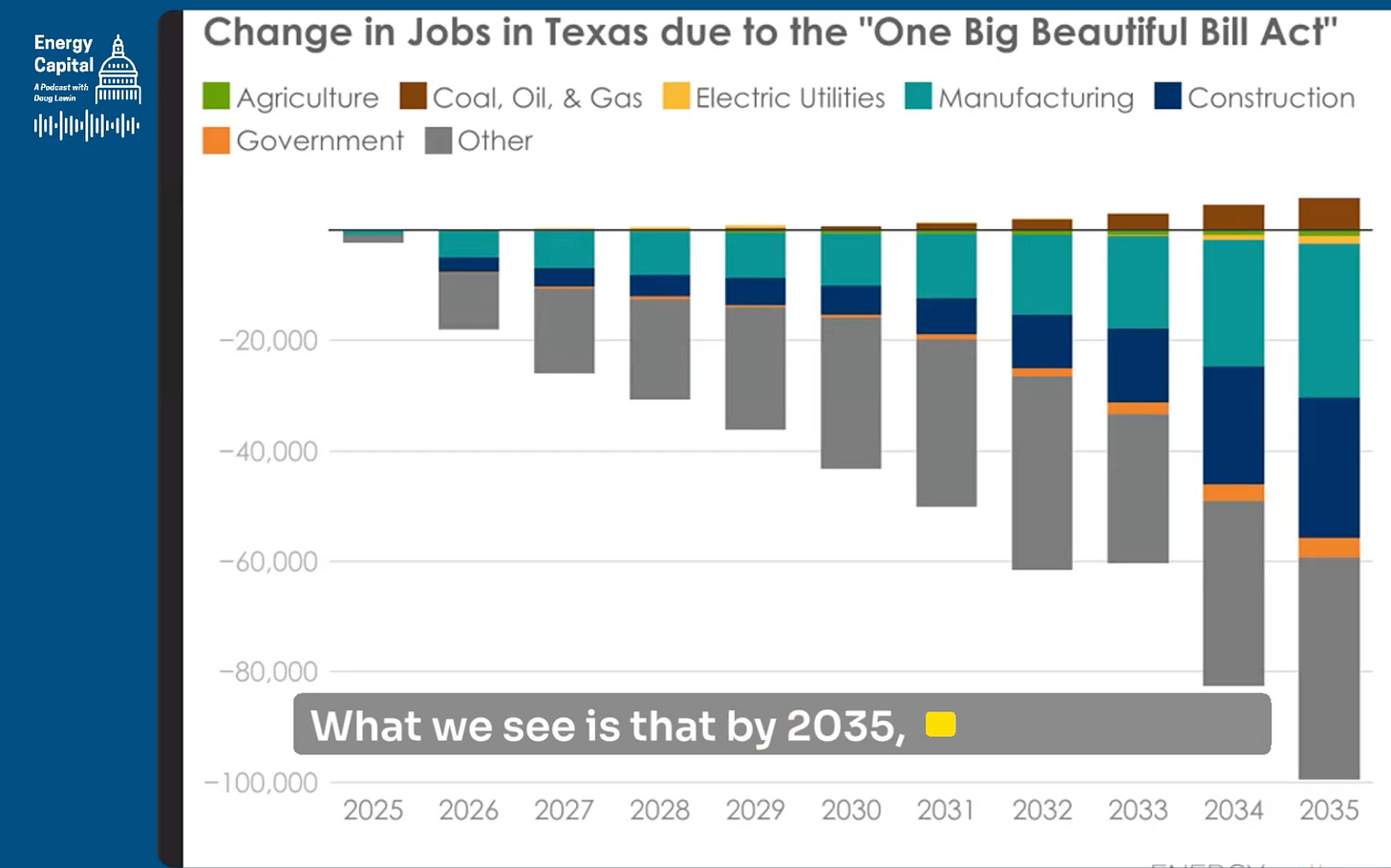

Very interesting. Okay. Let's talk about jobs as well. We've talked about the cost of power and what that might mean for investment and competitiveness. There's a whole lot of jobs in clean energy in Texas right now, and those were increasing significantly to the point where even there was a very interesting tweet earlier this year from Governor Abbott where he said, we had beat out California actually in the addition of wind and solar jobs earlier this year. And he was rightfully bragging on that. So we've really seen this make a big impact for Texas workers. What happens to jobs under the budget bill?

Dan O'Brien (25:46.228):

Like you said, renewables and clean energy generally powers a lot of the economy in terms of new job additions. I'm now showing on the screen here for those who aren't looking, a graph of the change in jobs in Texas as a result of the bill. And I have it broken out into seven different sectors. So agriculture, fossil fuels, electric utilities, manufacturing, construction, government, and other. And what we see is in 2025, there's very small impact from this bill because it takes time for utilities to update their planning and make different power plants. What we see is that by 2035, 10 years from now, Texas loses around a hundred thousand jobs in sectors other than coal, oil, and gas. And those three sectors, coal, oil, and gas, add around 6,000 jobs on the same time frame. The overall loss is around 94,000 jobs just in Texas alone. And like you just said, it's the biggest state for clean energy in the country right now. And this is kind of a big reflection of that reality is that losing clean energy does a lot more to harm the economy than gaining in coal, oil, and gas can.

Doug Lewin (27:10.648):

So that's about 30,000 manufacturing jobs, about 20,000 construction jobs. You got this other category. Is that, is a lot of that like wind technicians and solar installers and things like that, or do those fit into construction?

Dan O'Brien (27:24.632):

Those are probably mostly in construction, but other captures the induced impacts of these losses around the economy. So these are convenience stores on the corner that are shutting down because people aren't buying goods because the economy slows down. These are teachers and nurses and other folks employed around the economy that lose their jobs because clean energy is such a powerhouse in Texas that when that slows down, the rest of the economy shrinks.

Doug Lewin (27:55.278):

Particularly in Texas rural counties, right? I mean, I refer a lot to, and we posted it on the YouTube channel. There was a hearing around Senate Bill 819, which was the very onerous restrictive permitting bill that passed the Senate but did not pass the House. When they brought it up in the Senate, there was some great testimony. I highlighted in the YouTube video the testimony of folks from Armstrong County, Schleicher County, and Nacogdoches County. The first of those two, Armstrong and Schleicher, like 2,000 people and they literally have tens of millions of dollars of investment going into their schools and roads and all the rest. So we would obviously see much less of that. But it's interesting to me though, Dan, even if you were to discount all that, and I don't think that should be discounted, but even if somebody's listening and says, well, I don't know about all that, you've got 30,000 manufacturing jobs lost for 6,000 oil and gas jobs gained. Even if you just look at that piece of it, it's a terrible trade off for the state of Texas. This may work out other places okay, but it looks pretty obvious from the modeling. And again, yours isn't the only one. We're seeing pretty consistent results that this is a terrible outcome for Texas. And it's hard to imagine any elected official in the state of Texas supporting this kind of thing.

Dan O'Brien (29:11.628):

Yeah, that's right. It's pretty stark losses when you look at it around the economy. And even if you focus on one sector like manufacturing or construction, each of those on its own are two or three times, at least the losses that you see in the gains in the fossil industry. I think you point to a correct reality that rural communities are really the ones that are harmed the most from this. These are communities, especially where new power coming on is often from smaller companies, family-owned businesses that can't afford and don't have the capital to be resilient to big shifts in policy like this.

Doug Lewin (29:50.444)

Before I ask you if there's anything I should have asked that didn't or anything you want to say in closing, I will just say I think as the results of this bill start to become more more apparent, as people's electricity bills go up, again, depending on what kind of guidance Treasury gives, that could happen very quickly or it may take a couple of years. But either way, as the jobs start to be lost, as the manufacturing starts to move out of the state of Texas, even outside the borders of the United States, I think it's going to become very important for policymakers of both parties.

We've talked about a lot of the states that are going to see the biggest impact from this. I think of folks like Senator Moran and Senator Grassley and Senator Ernst and Senator McConnell from states like Kansas and Iowa and Kentucky, and even Cornyn and Cruz from Texas, trying to figure out how to create some kind of bipartisan policy. And you don't have to agree or disagree with this, Dan, this is my view of the world. If you're going to phase out the tax credits, and I actually think it's okay to phase them out, if it's actually a phase out, if there was actually a ramp, a slope downward, not a cliff. And I think that who's really going to end up at the bottom of that cliff are consumers and American manufacturers. And what we need to do is durably phase them out in a way that Democrats agree to so we don't get this whipsaw back and forth. I think the modeling that you guys have provided is really helpful for people to start thinking that through. As we start to see what happens and how that lines up with the models, I think it's just going to become so important to revisit this and come up with some durable policy. You can react to any of that you want or leave it alone if you like, but also let the listeners know anything else that you wish I would have asked you, anything else that you want to say in closing, Dan.

Dan O'Brien (31:38.838):

I mean, all I can do is agree. I think good policy is designed with quantitative backing, like the modeling that we're trying to do here. Good policy gives certainty to businesses around the economy. Good policy focuses on helping people. And this is not good policy. If it were done right, it would be just like you described. It's understandable to want tax credits to phase out over time as the industry matures and the US becomes a powerhouse in the clean energy industry in a different world. It's important to phase out government subsidization of that. It's important that these are industries that learn to stand on their own in the same way that it's important that the fossil industry eventually does so. And giving that independence while also making sure it doesn't happen by pushing them off a cliff is important to keep it from hurting consumers and burdening households like yours and mine with high energy costs and making people lose their jobs just to get the kind of policy you want in place rather than the policy that makes the most sense for individuals.

Doug Lewin (32:47.714):

Yeah, unless anybody thinks it's just impossible or hopelessly optimistic. I, first of all, acknowledge that it's maybe a bit of a long shot that this would actually be fixed. But I will say two things on that. One, there's still a lot that Republicans in Congress want to get done, like permitting reform, right? Senator Barrasso had worked with Senator Manchin in the last Congress. They didn't get that across the finish line. And number two, no matter what anybody says, I just don't believe that any policymaker wants to see electric bills go higher and American competitiveness get harmed. So I think as long as we can talk about those high level goals, and again, just like you said, Dan, a high level goal can also be ending subsidization. If that's your goal, you're better off doing it in a bipartisan way so it doesn't get reversed next time Democrats are in control. So maybe it's naive, maybe it's optimistic, but it's a little thread of hope or something that I'm holding on to. Anything else you want to say in closing, Dan? This was great. I really appreciate all the work you're doing at Energy Innovation. This modeling has been super useful to me. I've put it in the newsletter, so thanks for everything you do. Anything else you want to say in closing?

Dan O'Brien (33:53.966):

Just appreciate your having me on and happy to chat with you in the future or answer any questions from your listeners. So thank you.

Doug Lewin (34:01.016):

Thanks so much, Dan, appreciate it.

Thanks for tuning in to the Energy Capital Podcast. If you got something out of this conversation, please share the podcast with a friend, family member or colleague and subscribe to the newsletter at douglewin.com. That's where you'll find all the stories where I break down the biggest things happening in Texas energy, national energy policy, markets, technology policy. It's all there. You can also follow along at LinkedIn. You can find me there and at Twitter, Doug Lewin Energy, as well as YouTube, Doug Lewin Energy. Please follow me in all the places. Big thanks to Nathan Peavey, our producer, for making these episodes sound so crystal clear and good, and to Ari Lewin for writing the music.

Until next time, please stay curious and stay engaged. Let's keep building a better energy future. Thanks for listening.